Vietnam Moratorium Campaign Anniversary- 50th Anniversary, 2020

8 May 2020 marks the 50th Anniversary of the Vietnam Moratorium Campaign when more than 150,000 Australians from many different walks of life took to the streets demanding an end to conscription and Australia’s involvement in US-led war on Vietnam.

Unfortunately, not much has changed since May 1970. Australia is still in a close alliance with the United States and has continued to support and follow the U.S. into wars of aggression in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and currently there is danger of being drawn into a war on Iran or China.

Vietnam Moratorium Campaign commemorations will be held across Australia later in the year. The aim of the celebrations includes learning from the past and applying those lessons to the present as we continue to campaign for an independent Australian foreign policy from all big powers.

Commemorations during 2020:

Adelaide, 20th September 2020

To see what is planned in each State, contact the following people:

Brisbane: rgwyther@optusnet.com.au

Melbourne: rennis_witham@aapt.net.au

Adelaide: der_burke@yahoo.com.au

Sydney: homishdu@yahoo.com.au

Newcastle: bevanlramsden@gmail.com

Perth: Christopher.crouch@gmail.com

Alice Springs: ipan.alicesprings@gmail.com

|

Background-to-the-vietnam-war-the-U.S.-invasion-and-Australias-involvment-an-IPAN-podcast-Part-I

The-anti-war-movement-and-the-Vietnam-Moratorium-Campaign-an-IPAN-podcast-Part-II

Some Background to the Vietnam War and the Vietnam Moratorium Campaign to oppose it

Historical background to Vietnamese people’s struggle for independence

Vietnam had been a colonial “possession” of the French prior to the Second World War.

In September, 1940, Japanese troops invaded Vietnam allowing a puppet French colonial administration to operate but the French colonial and business interests departed. The Vietnamese people under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh and the Communist Party of Vietnam fought the Japanese military occupation. Following the defeat of the Japanese Imperialists, the French colonialists returned in force to restore their control as per pre-WW2 days. However in line with anti-colonial, pro- independence movements throughout the Third World at that time, a Vietnamese Independence movement emerged led by Ho Chi Minh and the Vietnamese Communist Party to seek and fight for, independence from the French. They were close to success in 1954 with the defeat of the French at Dien Bien Phu but the U.S. began to intervene and back their puppet regime in the South following a temporary partition of Vietnam at the 17th parallel subsequent to elections being held throughout Vietnam as part of an international peace plan. The U.S. prevented elections happening.

In the late 1950s, Ho Chi Minh organised communist guerrilla movement in the South, called the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (or Viet Cong). The NLF guerrilla movement was a well organised mass movement of South Vietnamese people fighting against the US occupation and for the unification of their country. North Vietnam and the NLF successfully opposed a series of corrupt U.S.-backed South Vietnam regimes and beginning in 1964 withstood a decade-long military intervention by the United States.

The US military build-up in the 1965-1975 period reached a maximum of half a million soldiers in Vietnam. The US requested Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War which began with a small commitment of 30 military advisors in 1962, followed by troop commitments by PM Menzies in 1965, increasing over the following decade to a peak of 7,672 Australian personnel. Politically Menzies “justified” the commitment by claiming it would stop the spread of communism south towards Australia; he called it the domino theory. “One country falls to communism and then the next, then the next and it will then be on our doorsteps”. The Australian government refused to recognise that the war in Vietnam was a war to liberate the country from foreign interference and win independence for the whole country.

A vicious war was waged against the Vietnamese people fighting for their independence. The United States dropped more bombs on Vietnam than all of Europe in WW2. Low estimates put the number of Vietnamese killed in this war at 1 million. Napalm, a fiery sticky substance, was rained down on villages burning villagers alive or inflicting hideous scaring for life. The U.S. dropped 338,000 tonnes of napalm on Vietnam. Allegedly to remove forest cover from the Vietnamese guerrilla fighters to expose them to US firepower and destroy rice fields, the US sprayed more than 20 million gallons of herbicides such as agent orange over Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos from 1961 to 1971. Because Agent Orange (and other Vietnam-era herbicides) contained dioxin in the form of TCDD, it had immediate and long-term effects including causing cancer and birth defects. The Vietnam Red Cross estimates that 3 million Vietnamese have been affected by Agent Orange, including 150,000 children born with birth defects. Following the end of the war, Australian returned servicemen fathered children borne with severe deformities considered to be the result of their exposure to agent orange.

The mass movement against the Vietnam War

As part of its preparations for sending troops to the war, the Menzies Government had earlier announced in November 1964 a “birthday” ballot national service scheme (Conscription) under which 20 year old males would register and the required number of conscripts would be drawn from a twice-year lottery.

The 1964-1972 anti-Vietnam war, anti-conscription movement was specifically aimed at ending Australia’s intervention in Vietnam and the associated conscription scheme. Opponents of the war were galvanized into action by the indiscriminate bombing and napalming of Vietnamese civilians, and the view that the war was a civil one rather than part of a “downward thrust” of “communism” towards Australia. The perception grew that this war represented a form of imperialism on the part of the United States and it became clear to many that Australia was supporting an undemocratic and repressive regime in South Vietnam. Opposition to conscription focused both on preventing young men being forced into such a war and on the coercive and militarist nature of the scheme itself.

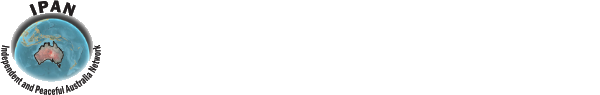

Whilst protest rallies and other forms of opposition to the war and conscription developed across Australia in the 1965 to 1969 period, many acts of civil disobedience also arose to raise the pressure on the Australian Government. Young men refused to register for “National Service” and defied call-up (draft resisters) risking fines and jail terms. Some were jailed and that stimulated further opposition to the war and conscription. Trade Unionists refused to load ships carrying military supplies to Vietnam. Maritime workers, railway and public transport workers, workers from many industries, public servants went on strike, held mass stop work meetings and passed resolutions calling on the government to end conscription and bring Australian troops home. Student protests and meetings were held across Australia’s universities. Statements were made in newspaper advertisements backed by hundreds of signatures calling for defiance of the National Service Act and in doing so the signatories risked jail themselves as it was a Crimes Act offence. Registration cards were burned publically; post offices, which distributed registration cards, were occupied and disrupted in protest.

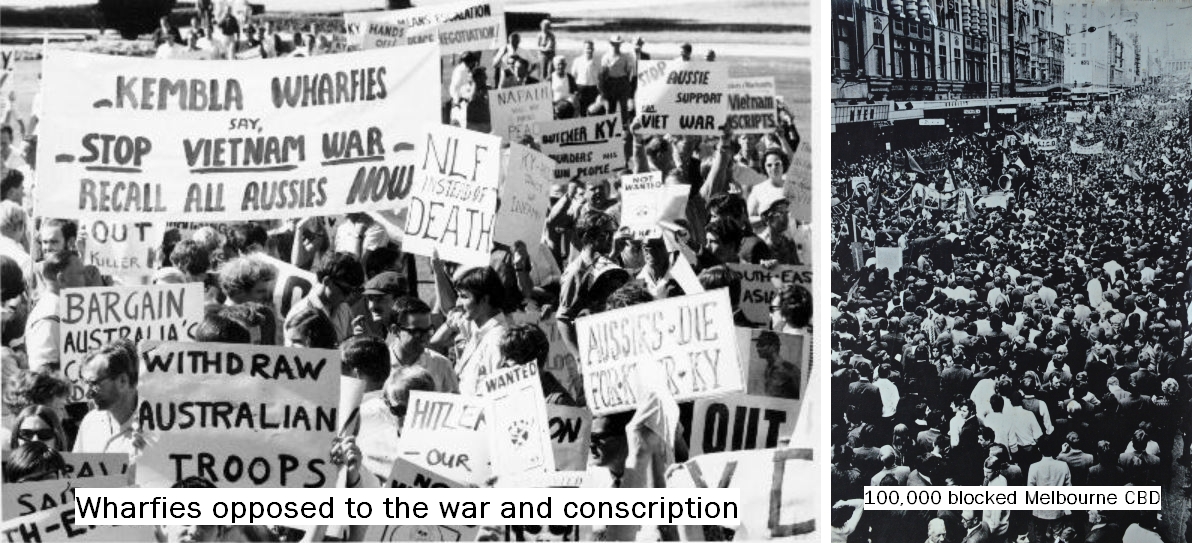

By 1969, it was recognised that the many protest actions would be more effective if coordinated in each state and nationally. From this awareness in a Melbourne peace organisation and spread nationally, an organisation called the Vietnam Moratorium Campaign was formed in each state with a national coordinating committee. Peace organisations, trade unions, church groups, student organisations and other community organisations affiliated with their state VMC’s. Under the general demand of ending conscription, bringing Australian troops home and opposing the war, national days of coordinated protest were organised. On the first national day of protest, 8th May, 1970, 150,000 -200,000 joined in protest marches; in Melbourne 100,000 sat down and occupied five city blocks in an act of group civil disobedience. Further national days of action followed in 1970 and 1971. Whilst the general call for an end to conscription and an end to the involvement of Australian troops in the war was the major rallying cry, groups and individuals were identifying the imperialist nature of the US war of aggression against Vietnam and calling for an end to the military alliance between Australia and the US which was responsible for drawing Australia into this immoral war.

These national actions and the broader anti-war and anti-conscription protests were politically successful, impacting on the liberal-coalition government which was forced to commence winding down Australia’s military involvement in 1971. But it took a change of government, to the Whitlam ALP government in 1972, to finally respond to the wave of revulsion against the war and conscription to rescind the National Service Act, bring home the remaining Australian troops and release those jailed for their conscription defiance.

Download this useful booklet giving more background on the Vietnam War and campaigns against it by activist and former Victorian politician Joan Coxsedge who was centrally involved in the campaign against the Vietnam war.

‘Taking to the Streets against the Vietnam War’: A Timeline History of Australian Protest 1962-1972